Spherical bearings are used in a wide variety of applications in motorsports. As a stand-alone bearing or as part of your typical rod end, they readily handle many different duties concerned with a race car. The rod end is most widely known for use for the spherical bearing design as used in steering, 4-link, and ladder bar assemblies.

We dove into the subject of these bearings with one of the foremost authorities on the subject, John McCrory with Aurora Bearing Company. Talking about all things spherical, he addressed many hardcore applications along with knowledge specific to these components as they are used on your race car.

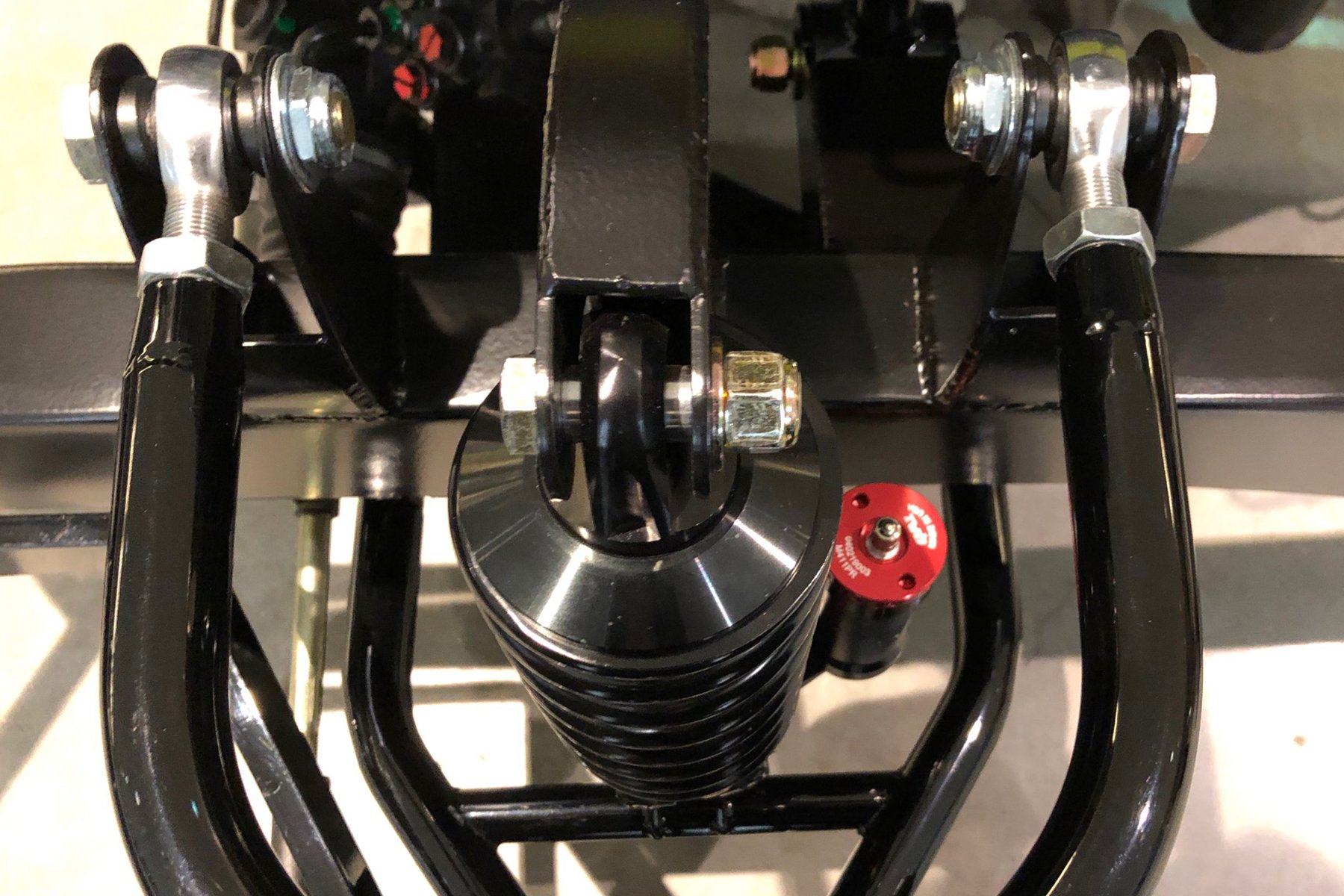

Spherical bearings are located throughout the typical race car. Applications include usage on top of the strut towers, coil-over shock ends, and many steering and suspension joints. The widely known rod end contains a spherical bearing within the male or female threaded rod end body.

Spherical Bearings Applications

A spherical bearing allows angular rotation about a central point inside of an outer body. These bearings can also move in an angular motion. For an example, this combination of rotation and angular motion connections is applied to suspension and steering mechanisms.

“Rod end and spherical bearings can be found in numerous locations on race cars, whether they are purpose-built, or replacing original automotive equipment manufacturer (OEM) components,” McCrory expands. “They are often associated with suspension and steering linkages, but also may be used in gear linkages, such as door hinges, or spoiler and bodywork mounts.”

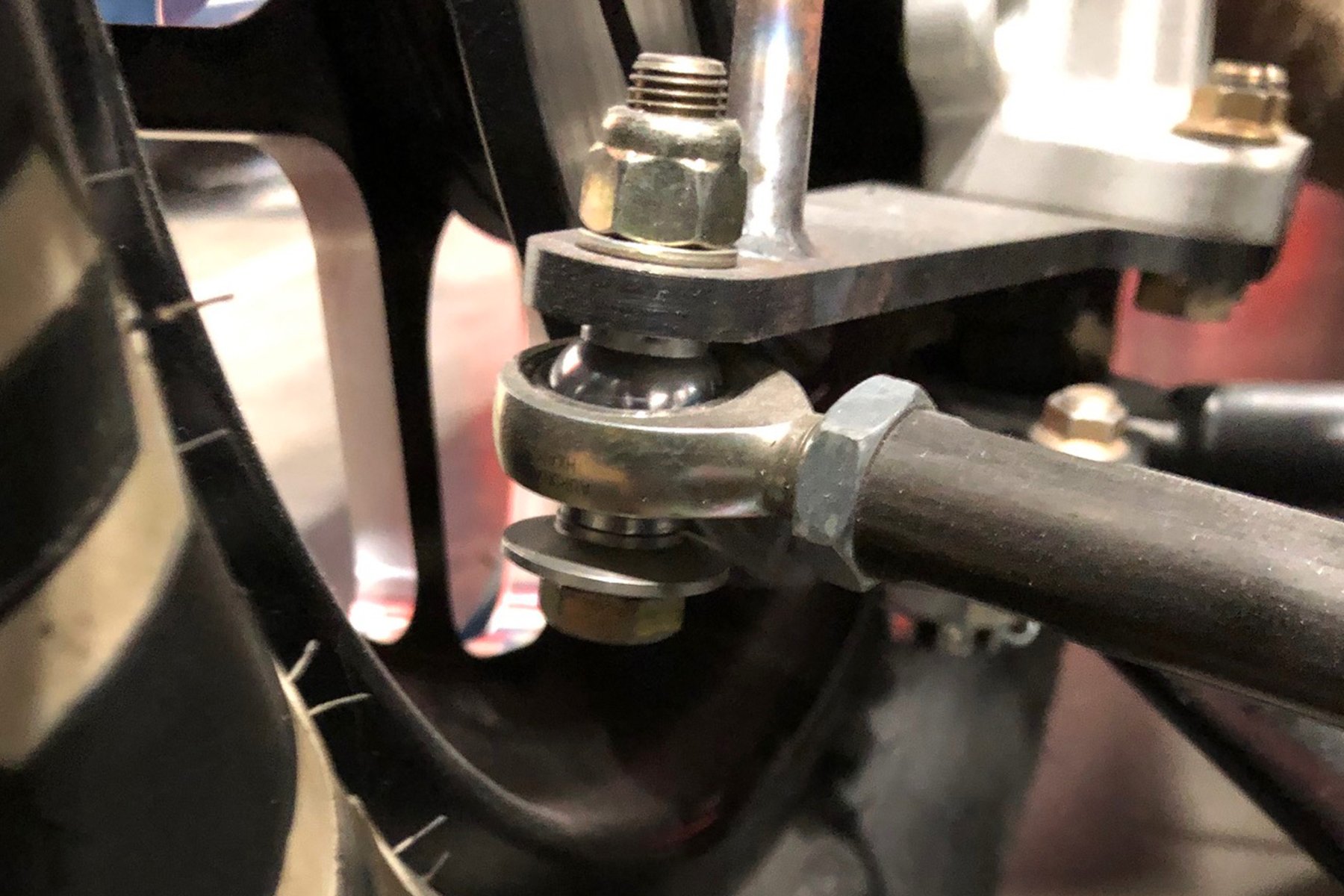

A spherical bearing is used in many front strut suspension designs to offer axial movement for the suspension. The same application is used for steering rod ends. Note the use of misalignment spacers to allow for more significant movement in the steering arms without binding of the rod end.

With so many different classes and levels within drag racing, we asked McCrory if there are any series applications of rod ends and spherical bearings as applied to specific classes. He responded, “In a racing application such as a full-time drag car or in Drag Week-style competition where their prime function is the dragstrip, the suspension should be treated as if it is a race-only car.”

McCrory goes further by explaining that with a street/strip car driven primarily as a street application, you might be better off with a urethane or similar suspension. However, when power levels reach a higher point, the inherent deflection that is possible will compromise the performance of the suspension design under extreme load.

It’s more of an issue to apply rod ends for the peak horsepower level your components must handle; by no means is there a generalized street or strip application. – John McCrory

Racing Applications

For racing, these bearings are often divided into two categories: suspension joints and secondary linkages.

Secondary or control linkages generally denote throttle, clutch, brake linkages, gear shift mechanisms, and other applications beyond suspension joints.

“These bearings are designed toward applications with low loads,” McCrory explains. “With little shock or high-frequency oscillation, the joints used in these applications are often low specification industrial/commercial grade rod ends.”

Compared to joints used for suspension and steering, the general specifications of rod ends used are relatively universal. The body, ball, and race are all constructed of steel, with the highest specification parts featuring a heat-treated body and race.

For entry-level or low power drag cars, 4-link kits are available that use inexpensive commercial-grade 4-link rod ends. These ends may be okay for some basic drag cars, but are not acceptable to handle any power versus hard-launching scenarios. So in this situation, a high-strength joint is a good performance update.

Shown are the three key components of a heavy duty rod end. The spherical bearing consists of a hardened alloy ball and race. In a rod end application, these are installed within a threaded body. The safety washer is required by rulebooks to prevent detachment of a steering arm in the possible event of a spherical bearing separating from the housing.

“Suspension and steering ends in nearly every purpose-built race car at medium or maximum power levels should use a liner-safe rod end,” McCrory instructs. These quality rod ends use a carrier fabric for strength, along with a Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) component for lubricity. This type of PTFE-lined rod end offers the optimum in stiffness, strength, and frictional characteristics at a cost-effective price.”

Rod End and Spherical Bearing Sizing

For the extreme application of ladder bar and 4-link suspensions, there are three most common sizes used in racing. These are denoted by the mounting hole first, and male thread second. In the typical 4-link rear suspension, these include ¾-inch hole x ¾-inch thread, 5/8-inch x ¾, or ½-inch x ¾-inch.

John McCrory from Aurora Bearing Company endorses the PTFE-lined rod ends to be used in all critical suspension applications, from bracket racing to Pro Stock. This cutaway view shows the precision PTFE liner incorporated into their high-strength AM-series rod end.

“Ladder bars are typically ¾-inch x ¾-inch on the chassis end,” McCrory describes. “For those cars typically produced by a professional builder or within chassis kits, these are the sizes normally used. There’s really no need to reinvent the wheel.”

He clarifies further by noting specifying rod ends is not just about the size. “Once you determine or confirm the sizes, the prudent way to go is to choose a bearing with plenty of strength,” he says. “For rod ends, that will mean a heat-treated alloy steel body.”

He adds, “We mentioned the PTFE-lined rod ends for suspensions and steering. We strongly consider these for their zero clearance, self-lubricating, and low friction under load.”

This 4-link and anti-sway bar system illustrate the various rod end sizes used in racing chassis. There are countless brands and rod end part numbers out there. Do not confuse a "good deal" on some rod ends that may be inferior for high-stress applications. Though they may appear similar on the outside, these rod ends do not contain the PTFE liner or a hardened bearing race around the ball.

Calculations

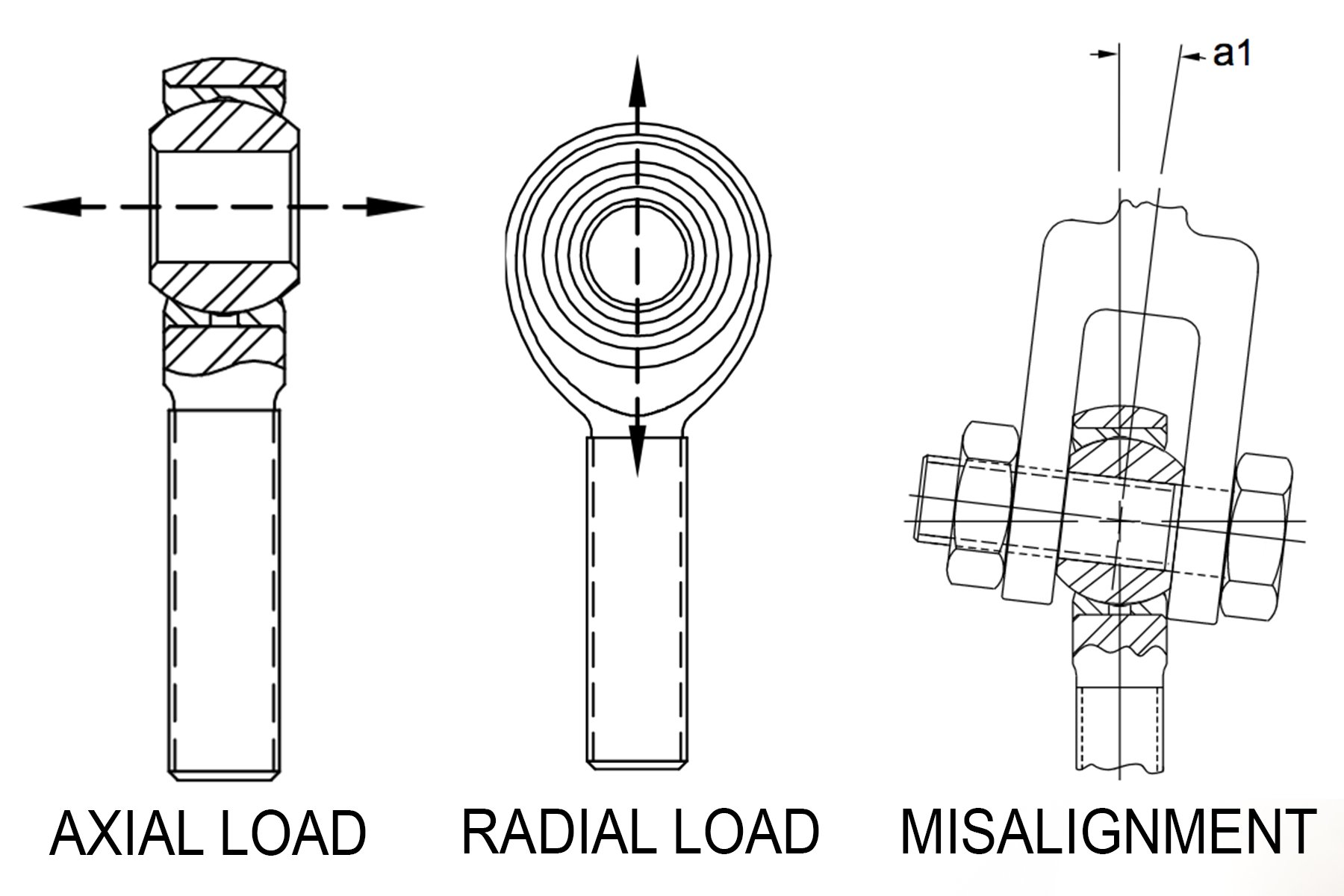

An informative rod end catalog such as the one available from Aurora Bearing includes specifications for “radial static load capacity.” As that capacity is providing universal specifications for these bearings, McCrory offers some definition to that term.

“This load capacity basically is defined as the amount of load, applied either radially or along the axis of the threaded portion of the rod end,” he defines. “In a tension load, that will cause the part to fracture or fail. In a radial load, it is recommended that the capacity spec be no more than 25-percent of the rated radial load.”

Bearing catalogs can offer a wealth of information on not only availability, but critical dimensions, load characteristics, and maximum misalignment angles provided by various part numbers.

Axial loads, which are loads through the axis of the ball or 90-degrees from the axis of the shank, are typically recommended to be about 10-percent of the radial load number.

Designing Around Rod Ends

If you want to construct or rebuild any mechanism around the spherical bearing for your racecar, remember that rod ends are designed in sizes to accept industry-standard dimensions.

These size options are not necessarily made to sizes typical in the automotive industry. They will likely not bolt in and will require adaptation on your part. The popular Ford Pinto rack and pinion has a tie rod thread dimension that does not mate within a standard production rod end.

Remember there is no shame in the S and C (stare and compare) method. Look at other cars of the same or similar type, and ask questions regarding the unique applications. – John McCrory

Wear Life

“The wear life of seemingly similar bearings can vary greatly from different manufacturers,” advises McCrory. “This can be due to design and manufacturing control, and often attributed to the make-up and installation of the PTFE liner.”

He continues, “That liner is a wearable component, just as a brake pad or clutch disc. There is a big difference between discount parts store brand and proper high-performance brake pads. The same longevity applies to PTFE liners from different bearing manufacturers.”

The most significant wear criteria will be the quality of the bond between the liner and bearing raceway. Again, ask racers or leading chassis builders who use different manufacturers for their observations and input on brands they use.

Maintenance

Taking care of your spherical bearings is a matter of monitoring for wear and damage. Since they are not rebuildable, you need to replace them when the time comes.

“Racers using the PTFE-lined rod ends or spherical bearings need to understand these components use zero clearance when manufactured,” McCrory continues. “With your car up on jack stands, put your finger between the body of the rod end and the bracket, and start giving it a good shake, and if you feel movement relative to the two, it’s developing clearance.”

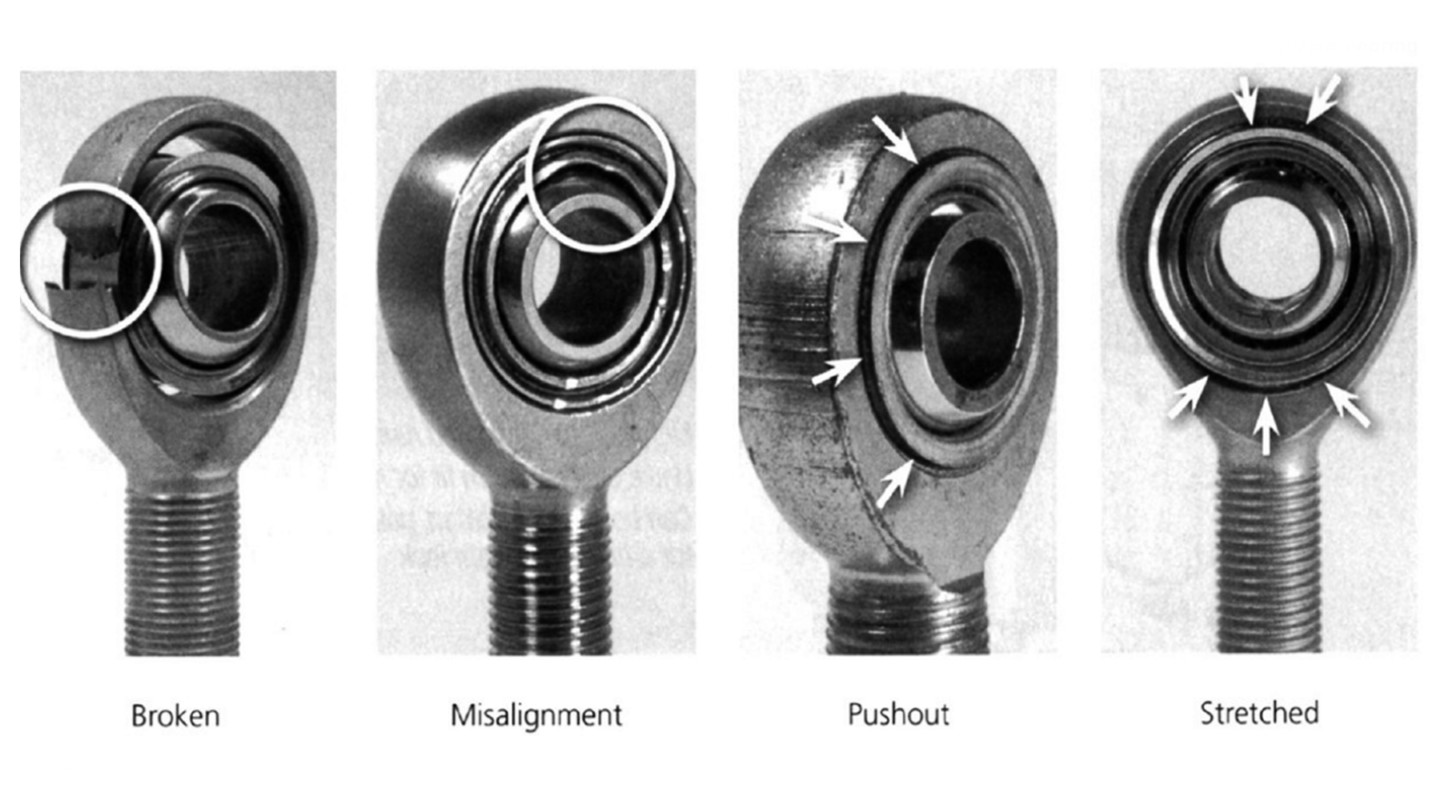

This Aurora Bearing illustration shows some of the most common failures to look for when you inspect all spherical bearings and rod ends on a regular basis.

“With metal-on-metal rod ends, for example, it’s a lot harder to perform a shake test. There is always a degree of clearance even with a new rod end. So, you need to be a detective and look for other clues,” McRory says.

One of the rules of thumb is to remove and thoroughly clean any spherical bearing. You should be able to feel and hear a slight rattle if the tolerances are getting too high. But McCrory stresses the need to inspect for evidence of overload on the ball itself visually.

“The key is to look at the color and surface finish of the ball,” he says. “When you start running metal-on-metal, you start heating the ball up and it will start discoloring the chrome on the ball. Progressively, it goes from shiny to brown to black as it heats up further and further. The next step is galling or micro-welding.”

At a microscopic level, the ball and the race can actually weld together where the ball surface gets rough. McCrory continues, “People will take a rod end from a 4-link suspension and claim it needs to be greased more because of grit and marks on the ball.”

“Compared to a lightly worn bearing, this wear is called adhesive wear,” McCrory illustrates. “What is actually happening is on a microscopic level. The ball surface is welding to the race and breaking loose. The broken welds give the appearance of roughness."

Racers may think that these examples of visible wear happen in more of an endurance application such as circle track racing, but that is not the case. “This wear doesn’t occur over time, it occurs by the extreme load,” McCrory says. “More wear can occur at the first 100-feet of a dragstrip compared to an oval track car.”

Many other common-sense inspection points include rod ends or stand-alone spherical bearings that are damaged due to extreme misalignment during motion, thread wear, or wear to the body surrounding the spherical ball. These are preventative measures that fall under the inspection of all race car fasteners.

The Number One Enemy: Tire Shake

“Tire shake is the thing that separates the men from the boys when it comes to the suspension rod end,” McCrory asserts. “I’ve seen 4-link joints removed from a two year-old Pro Stock car that are still good. On the other hand, I have seen rod ends from a Pro Modified that has a tire shake monkey on its back that are relatively new yet are worn out. In that case, we recommend our military-spec rod ends for such extreme applications. They contain a heat-treated steel bearing race, among other features.”

Get What You Pay For

When it comes down to brass tacks, a quality rod end or special bearing is just like any other racecar component. The temptation to get a deal on such hardware may be tempting since they all can have a similar appearance, but there is a reason that the saying, “you get what you pay for” is so valid.

As much as choosing proper components to put your safety first and foremost, an equal amount of effort is necessary with monitoring all of these components as an exercise in preventing failure.

McCrory finishes, “At the end of the day, you will discover that a good rod ends cost good money. You are buying a precision machined component that takes plenty of abuse in many different ways. Consider these as critical parts that you are placing a lot of trust within.”