Participation in a competitive auto racing series is an immensely important endeavor for auto manufacturers the world over.

Amongst the benefits racing offers is a test bed for cutting-edge engine, chassis, aerodynamic, and material technologies, the promotion of a brand’s competitive ethos, and a means of advertising that far exceeds the effectiveness of print or television alone.

Here in America, the Big Three automakers, Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler, have always taken their racing seriously, allocating massive amounts of money and resources to pursue these returns.

Perhaps at no time was this more evident than in the world of 1960s NASCAR racing. During this period, the Big Three fought tooth and nail against each other for winner’s circle glory, and to hopefully prove the adage, “win on Sunday to sell on Monday.”

The NASCAR rules of the time stipulated that for a manufacturer to race a particular type of car, they had to build and sell to the public a certain number of street-going “homologation specials” that incorporated many of the race car’s specs.

This regulation had the effect of being the impetus for some of the wildest street cars of all time, and Ford’s contribution consisted of the 1969 Torino Talladega, a sleek, aerodynamically efficient beast possessing a powerful, big-block lump.

In this iteration of Rare Rides, we’re going to examine the history, mechanicals, and legacy of the Torino Talladega in an effort to gain a full understanding of this remarkable car. I’d love it if you decided to join me!

In the mid-to late-1960s, Ford was in a bit of a quandary. While the company had famously defeated the Ferrari juggernaut at Le Mans in 1966, at home in the States where it really counted, they had been having their lunch routinely eaten for them in NASCAR by the monstrously potent, Hemi-powered, Dodge, and Plymouth cars.

After Mother Mopar completely dominated the 1964 season, NASCAR officials responded by slapping a host of weight and class restrictions on the Hemi cars. In spite of this, they continued to be amongst the most formidable cars on the track year after year. 1967 was even more lopsided than ’64, with Richard Petty’s Plymouth Belvedere taking the championship, and Dodge and Plymouth cars racking up a combined 36 wins to Ford’s ten.

Ford executives were not pleased.

The 1967 NASCAR season was dominated by Richard Petty and his Plymouth Belvedere. (Photo courtesy of David Bryant.)

Their reaction was to up the ante and produce a full slate of redesigned models for the 1968 NASCAR season consisting of Mercury Montegos, Cyclones, Ford Fairlane 500 fastbacks, and Torinos.

The latter was based on FoMoCo’s newest street car, the Torino, which was the high-end trim model in the Fairlane line. Available in two-door hardtop, two-door convertible, four-door sedan, and station wagon configurations, the Torino rode on a unibody chassis developed from the previous generation Fairlane’s platform.

A conservatively handsome car featuring a full-width recessed grille encompassing quad lamps and neatly creased flanks, the Torino offered luxury and sportiness in one package.

This was especially true in the case of the range-topping Torino GT. Available only in two-door coupe, elegant fastback-style “SportsRoof,” and convertible forms, the GTs luxury items included lower bodyside moldings, special emblems, deluxe wheel covers, and an upgraded interior.

Mechanically, the GT could be outfitted into true muscle car spec, with big 390, 427, and 428 cubic-inch Cobra-Jet V8 motors on offer, mated to your choice of a four-speed manual or a C6 slushbox. Putting power to the ground was an 8- or 9-inch diff with 3.91:1 or 4.30:1 gears spinning 28- or 31-spline axles. A Competition Suspension Package, which included extra-heavy-duty springs and shocks, as well as a stout front anti-sway bar rounded out the performance options.

The redesigned Fairlane line, including the Torino trims, was warmly greeted by the automotive press and the car-buying public, with 371,787 cars moved in total, 172,083 of them Torinos.

In NASCAR guise, the SportsRoof Torinos, while experiencing a power deficit to the Hemi cars with their 427 cubic-inch Ford race engines, nonetheless acquitted themselves superbly owing to superior aerodynamics. Ford cars achieved 27 victories out of 49 races during the 1968 season, with lead driver, David Pearson, securing 16 of those wins and the NASCAR Grand National title.

Despite this, it was very close on track with the Chrysler cars all season. Plymouth and Dodge won the remaining 21 races, and Plymouth driver, Richard Petty, tied Pearson on 16 wins.

With engine development beginning to yield diminishing returns owing to technological constraints, the outcome of the 1968 season made it clear that larger speed gains could be had by concentrating instead on aerodynamics. An “aero war” was brewing in NASCAR, and both Ford and Chrysler would be leading this charge into the 1969 season.

In the fall of 1968, Ford, in conjunction with race car manufacturer and NASCAR team, Holman-Moody, began work on their ’69 contender. While it was to be publicly referred to as a Ford Torino Talladega after the newly opened Superspeedway in Alabama, the basis of the race car would actually be the Fairlane Cobra model with a SportsRoof body.

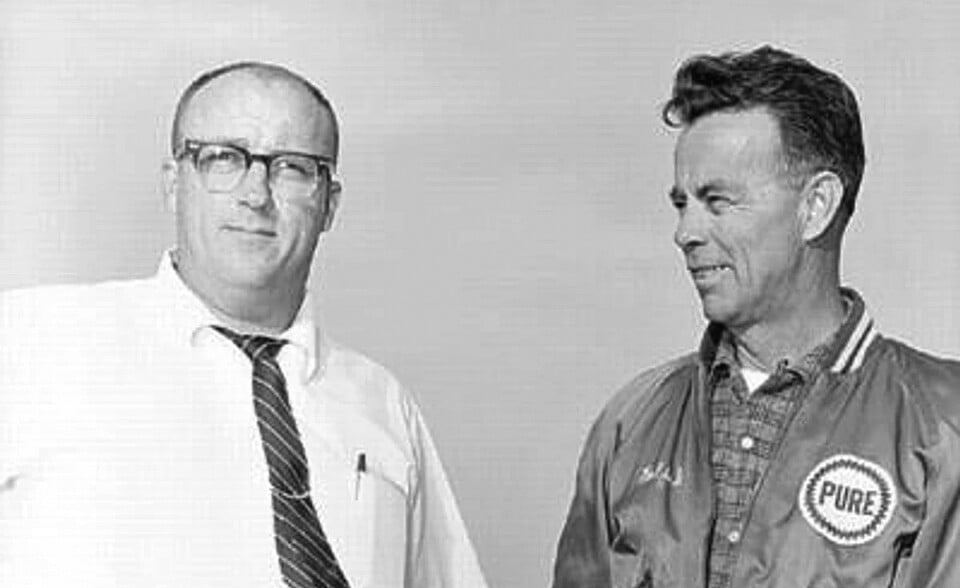

Ralph Moody, co-owner of Holman-Moody, along with Ford engineers, utilized a Michigan wind tunnel to design a modified body package for the car.

Starting at the front, Moody designed a completely new nose that extended the overall length of the car by six inches. Affectionately nicknamed “the drop snoot,” the new design introduced a 30-degree slope to the nose to better pierce the air and direct the flow over the car. The recessed grille and headlights of the street car were brought forward and made flush with the front to reduce turbulence. These changes alone were said to be good for a five MPH increase in top speed, the equivalent of a 75 horsepower gain.

A new front bumper was fashioned out of a Fairlane rear bumper which was cut and bent into a V-shape in an effort to reduce the area of the stagnation point and redirect the airflow. Mounted flush with the leading edge of the grille, the bumper’s shape provided for an ersatz air dam, which offered a degree of downforce at speed.

Other modifications to the Talladega included hand-shaped front fenders and bespoke rockers that were reprofiled and rolled, which enabled Ford to run its cars an inch closer to the ground than before. The lowering improved downforce and enhanced the cars’ top speed by virtue of reduced wind resistance and a lower center of gravity.

Under the hood, the Talladega racers were initially outfitted with the venerable Ford FE 427 cubic-inch side oiler, but later in the season, the new Boss 429 motor was used by most teams.

In January and February of 1969, Holman-Moody employees assembled the race cars at the Ford Motor Company Atlanta Assembly Plant on weekends, when the regular production line was shut down. Though it was a tight schedule, the Talladegas were ready for the beginning of the ’69 NASCAR season.

From the very start, the Torino Talladega proved to be a juggernaut on track, enough so to lure Richard Petty away from Mopar after the third race. By season’s end, Ford had achieved its goals – Talladegas won a total of 26 races, with Cyclones bringing in another four, compared to Dodge’s total of 22. Racing a Talladega, David Pearson again took home the championship, with Petty right behind him in second.

The Talladega homologation street cars were no slouches either.

On the outside, they received all the tricks of the Holman-Moody racecars – the elongated drop snoot, the flush headlights and grille, the bespoke bumper and fenders, and the unique rockers. Exterior colors were limited to three choices: Wimbledon White, Presidential Blue, and Royal Maroon, with all Talladegas leaving the factory wearing a flat black hood and tail panel.

Stark exterior ornamentation merely included Ford lettering front and rear, a faux gas cap emblazoned with a large, blue “T”, and a sizable, chrome “T” above the door handles.

The drop snoot, flush grille, and bumper transplanted straight from the NASCAR Talladegas. (Photo courtesy of Mecum.)

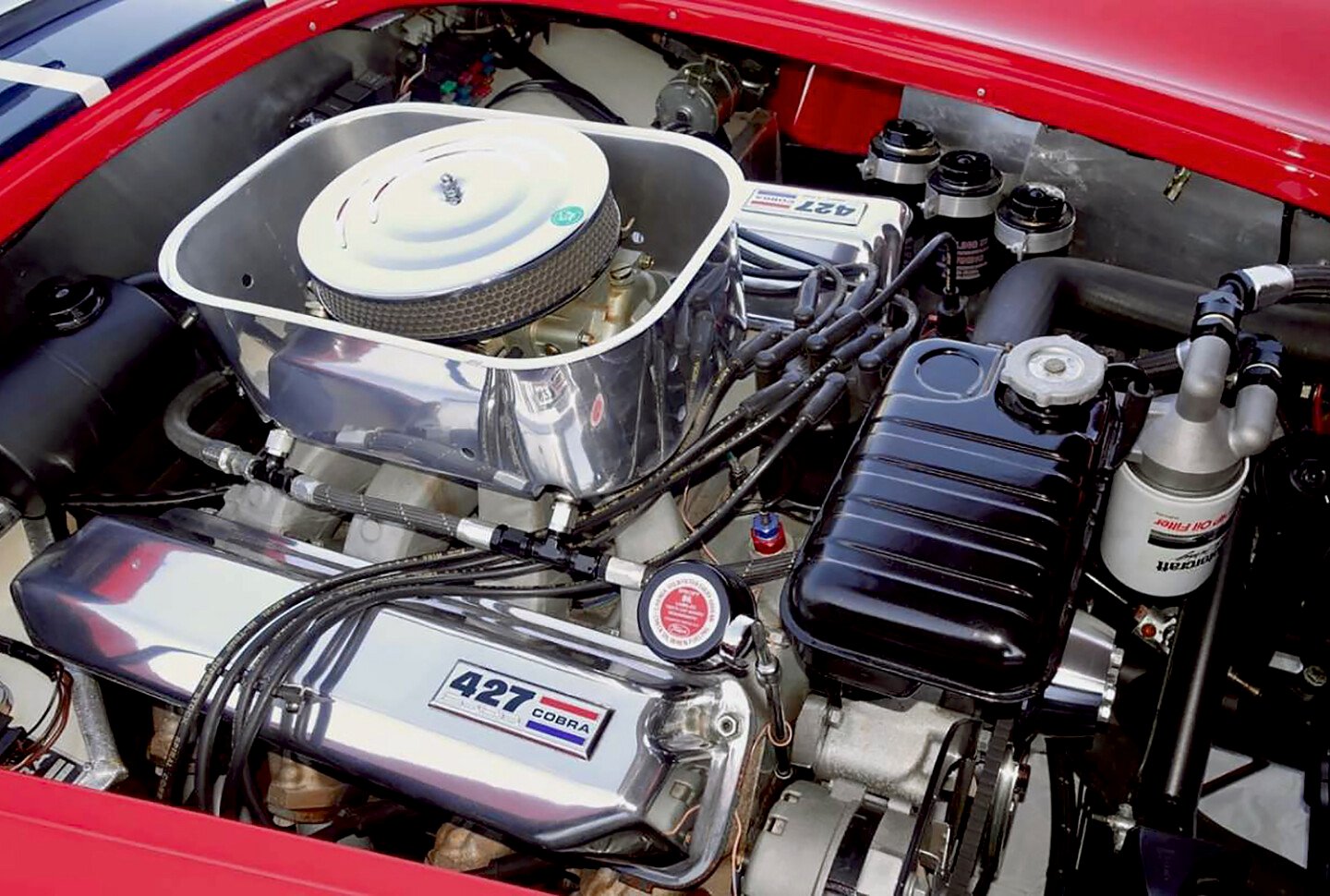

When it came to the powertrain, the streetcars differed mightily from their track brethren. No 427. No Boss 429 either. Instead, Ford felt that the best engine for the Talladega would be the 428 Cobra Jet V8, owing to its superior streetablility over the former lumps.

A relative of the 427, as it was an FE series motor that borrowed the 427’s low-riser head design, the 428 was an easier engine for the average driver to get the most out of due to its massive torque availability at low RPMs.

Ford considered the big 428 Cobra Jet a superior engine for their street Talladega to the 427s and Boss 429s. (Photo courtesy of Barrett-Jackson.)

Standout features of the Cobra Jet included a cast-iron block and heads, a bore and stroke of 4.13 x 3.98 inches, a 10.6:1 compression ratio, a cast-iron crank, high-strength forged connecting rods, a cast iron intake manifold, a dual 2.25-inch cast iron exhaust, and a single, 735 CFM Holley four-barrel. Special Talladega ancillaries included an engine oil cooler and a power steering oil cooler.

Output was listed at 335 horsepower at 5,200 RPM and a stump-pulling 440 lb⋅ft at just 3,400 RPM. Ford had underrated the power figures for insurance purposes though, and in reality, the engine was likely churning out close to 450 ponies, bone-stock from the factory.

Wimbledon White was the most popular of the three color choices available. (Photo courtesy of BringATrailer.com.)

Backing the Cobra Jet was a heavy-duty, column-shifted, three-speed C6 Cruise-O-Matic slushbox with a cast-iron tailshaft for added durability. Putting all that torque to the ground was a 9-inch, 31-spline, Traction-Lok limited-slip diff with 3.25:1 gears.

The Competition Suspension that was standard on Talladegas consisted of independent, unequal-length control arms, coil springs, telescoping shocks, and an anti-sway bar up front, with a live axle with semi-elliptical leaf springs and staggered telescoping shocks in the rear.

For coming to a halt, Ford provided power-assisted, hydraulic 11.3-inch front discs, and 10-inch drums out back. Styled steel wheels measuring 14 x 6 inches lived at all four corners and were mounted with Firestone bias ply F70-14 rubber.

Inside, street Talladegas were barely more luxurious than their racing counterparts. Citing weight-savings, Ford outfitted all the cars with what amounted to a spartan, all-black, taxicab interior: base cloth and vinyl appointments, a rather unergonomic front bench seat, and a standard complement of gauges including speedometer, tachometer, gas, oil pressure, and water temp. Even an AM radio was an extra-cost option.

With their potent powertrain, agile suspension, and lack of weight-bearing luxuries like air conditioning and lush appointments, the Talladega was quite a performer for 1969. A period automotive publication tested one as being capable of a 5.4-second zero-to-sixty sprint, a 14.1-second quarter at 101 mph, and a 130 mph top speed.

Though NASCAR rules at the time only required a homologation of 500 cars, Ford opted to build 754 instead, including several prototypes, pilot cars, and a special post-production one-off for Ford Motor Company president, Bunkie Knudsen.